“I didn’t plan to become a psychiatrist,” said James P. Comer, M.D., M.P.H., the Maurice Falk Professor of Child Psychiatry at the Yale Child Study Center. “It was the only thing in medical school that I said I would never do – public health was the other – and I ended up doing both. As I worked, I began to see that the individuals were being impacted by history, by political economics and social conditions that they have little control over, and that impacted the ability of families to function, the ability to rear their children well, the ability to participate and feel belonging in society – and that was related to racism. And in my own life experience, I had realized it, and I had been taught and raised in a way that I was not supposed to let racism stop me. I was supposed to get through and get the tools and equipment to make America a better democracy so that it would deal with racism.”

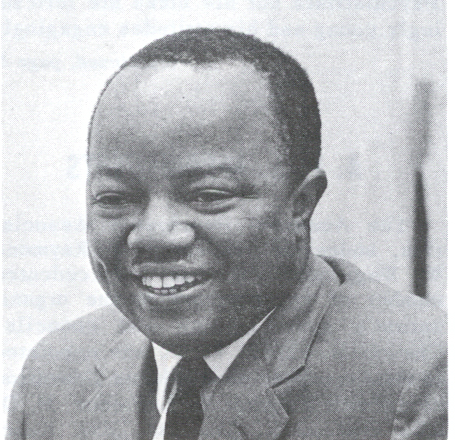

In addition to driving an illustrious career in child and adolescent psychiatry, Dr. Comer is one of the founding members of Black Psychiatrists of America (BPA) and served as President of the BPA in 1973. He will turn 90 this year but remains a member of BPA and of the Yale School of Medicine faculty. In honor of Black History Month, the American Psychiatric Association Foundation (APA Foundation) sat down with Dr. Comer to discuss his monumental role in the societal progress of Black psychiatrists and the Civil Rights Movement at large. To learn more about the history of Black psychiatry, visit a new exhibit at the APA Foundation’s Library and Archives.

Dr. Comer attended his first American Psychiatric Association (APA) Annual Meeting in 1965, while he was in residency. The Civil Rights Movement, particularly the late 1960s, was a crucial period for the small but growing number of Black psychiatrists to build momentum toward creating their own community within the field. “It was that three years of meeting informally that led to the letter to the Trustees of the APA, which then led to the first informal caucus event, and then, eventually, the sanctioned caucus of the APA.”

Like the broader struggle for racial equality, the movement towards equitable representation in medicine was hard-fought. The members of the informal caucus did not have the luxury of giving into despair. “It was the day of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. That day, we had a meeting of people who had been selected to plan the preparation of that letter [to the Trustees of the APA] and the preparation of the confrontation. We were in New York that day, and I remember – it's hard to describe anymore – the emotions and the feelings and the outrage and the crying and the yelling. People just let it all out,” said Dr. Comer. “And the determination to make a change came out of that. We were on our way anyway, but that just deepened the commitment.” The following year, 1969, Black Psychiatrists of America was co-founded by Dr. Comer and his colleagues, including Chester Pierce, M.D., in honor of whom the APA Foundation facilitates an annual award.

Despite being deeply involved with the APA and the BPA, Dr. Comer extended his advocacy to every corner of the mental health arena. He was responsible for the creation of the National Institute for Mental Health’s Minority Center. “While I was at the NIMH finishing up my career in child psychiatry,” he said, “I observed that there were very few grants given to African American researchers. I also observed that there was a difficult pathway to being heard within NIMH. I wanted to get to a place where people were going to be heard and seen and listened to. It was very important to be listened to, because the other problem was not that people who were not Black could not treat Black patients, but that they had not had the Black experience, and they did not know the community. That’s why we wanted a minority center.” What is now known as “culturally competent care” would not exist today without this groundwork laid by Dr. Comer and his peers.

Dr. Comer’s legacy lives on today in the NIMH’s Center for Minority Group Mental Health Programs, founded in 1970. In addition, the Black Caucus became the first of several affinity groups for minoritized communities in psychiatry that are hosted by the APA. And Dr. Comer remains active in the field, contributing a chapter to the 2024 APA publication Mental Health, Racism, and Contemporary Challenges of Being Black in America.