Q: Tell us about your work and how you came to be involved with the APA Foundation.

A: Well, the SALT Initiative started in 2015. The acronym came from the question of “How do you want to live this life?” It’s about service to others, affirming others, and loving others with kindness and compassion. That's transformative. That's SALT. I think we all should be a little salty, in a good way, to change the flavor when you walk into a space. Just recently in March, I officially came on board as a consultant for the APA Foundation to help modify our Notice. Talk. Act.® program and change it into a faith-based module. I’m excited to see how we can bridge faith and psychiatry so that they’re complementary, instead of being seen as in opposition to each other. I’ve also been working with Rawle and others involved in the My Brother's Keeper project, in our effort to reduce suicide in the Black community, especially among young men and men. Lowering that rate is so very important, and it starts with awareness. It starts with removing the shame and the guilt, and all those things that can come along with talking about one's mental health.

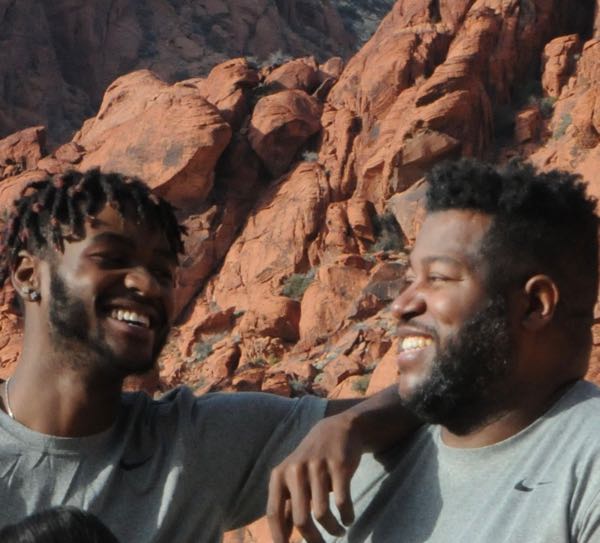

Q: The APA Foundation’s My Brother’s Keeper Project aims to support the mental health of Black men and boys. Tell us why you are involved in My Brother’s Keeper.

A: I've been doing Mental Health First Aid since 2008, and I’ve found that a lot of folks want help, but they don't know how to ask for help. And on the other hand, folks want to help, but they don't know how to help. The challenge is to bring those people together.

My youngest son has a birthday coming up. He will be 26 years old, but he had his first suicide attempt at 17. At that time, I had been doing Mental Health First Aid for a while, and my family had a suicide prevention magnet on the refrigerator. My family was aware of depression and all the other things that come along with it, but as my youngest son said at the time, “I just wanted the pain to stop.” With that first attempt, we all went and got tattoos of a semicolon. The semicolon speaks of how life continues. We memorialized that moment of saying that life continues, and out of that moment, I co-authored a book with a friend and colleague of mine called Bottled Up: Inside African American Teens and Depression.

We want to be able to support people by hearing their truth. If we cannot hear people, we cannot help them. What I learned by way of helping my son and others is that when I hear them truly, then I can engage them. And then once I engage them, then I can really learn from them. The HELP model begins with hearing people, then engaging people, then learning from and with them, and finally, the P in the model stands for planning with them. It all starts with holding space, just being open to whatever that person has to say. Because that's what everybody wants, eventually: Can someone just help me?

Q: How can we change the culture to make more psychological safe spaces for Black men and boys to be candid about their emotions?

A: I think that one of the things that it begins with is the socialization of what it means to be a man. These things are at the root. For example, when little boys fall down and they skin their knees, they’re taught to suck it up. What you're taught immediately, at that point, is that when you are in pain, don't complain about it. Don't talk about it, ignore it, because manliness means bottling it up. If you display emotion, then that can be considered weakness, and you may even receive a punishment. So either you suck it up, or you're going to get in more trouble.

What happens, of course, is that over time, all those things become bottled up. And we all know that when you shake anything that's carbonated, then it will explode. Here's a prime example: I went to the store, and I was looking for lemonade, because I don't drink soda. I said, Oh, this is a strawberry lemonade, and I just grabbed it -- but I didn't realize it was carbonated strawberry lemonade. So I went to shake the bottle, opened the cap, and it exploded. And there are certain life events that will happen to a youth that will shake them up so bad that everything on the inside of them will bubble over. And then, the bubbling over will be seen as aggression, and they are punished.

So, again, it begins with how we socialize Black children, to deal with emotions. We have to create spaces where they can safely express how they're feeling without fear that they will be judged or criticized or punished. Looking at those young African American men from a trauma-informed lens, we change the question of “What's wrong with you?” to “What happened to you?” And it is those adverse childhood experiences that increase the risk factor for mental health and addiction challenges. The better we can understand the adversity and the pressure that young Black children and men are dealing with, the better we can then try to address those pressures in a positive way and begin to deal with the despair.

I believe suicide is because of a hope deficit. When one loses hope within themselves, and hope within their community, and no longer has a hope to live, then there’s no path forward. Thusly, to end the pain, they often turn to ending the life that’s causing the pain. So we need to hold hope with young people and say, “I’m here with you to walk alongside you. You’re not alone. You are loved, you are cherished, you are important.”

Rev. Alberty recently appeared alongside Rawle Andrews, Jr. on the Let’s Go Show with Douglas Reed to discuss My Brother’s Keeper. Listen to the podcast to learn more.